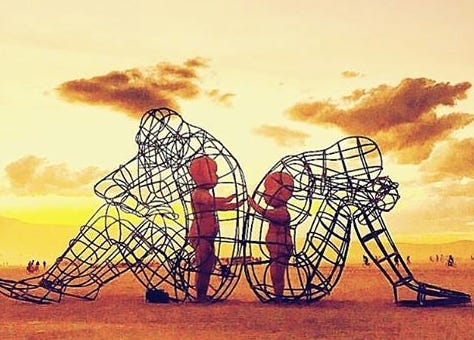

Disconnection and Democracy

Part 2 of 4

This is the second of a four-part series asking what precisely is going wrong with democracy. This is not necessarily saying that democracy is dying; rather, I am arguing that it is in crisis. These two ideas, oftentimes lumped together, remain inherently different. The former claims that there is a threat to democracy’s existence in some way, whereas t…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Theory Matters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.