The Death of Conservatism?

Part 2: A confused ideology in crisis

(British Conservative intellectual Roger Scruton)

In my first post in this short series on conservatism, I located danger in our political time. Liberalism has not resolved conflict, negated the desire for domination, nor provided unlimited prosperity for the citizens of Earth. In liberalism’s failings, or rather the failure of politicians to operate liberalism effectively, a philosophical opening has emerged to fill the vacuum.

That vacuum consists of a failure to provide meaning more generally in society. Our fixation on happiness and the distinction between two roads — expanding choice and limiting choice — highlights a deficiency in our political climate. Conservatism in the anglosphere has built on top of this claim and fails to address the dangers of our time. Instead, anglosphere conservatism has become a reactionary force which is inconsistent, unclear, and lurching towards authoritarianism.

Universalism and abstract values are in retreat as people are panicking. Democracy does not appear to be solving crises in housing, education, jobs, or material prosperity. The economic boom between 1945 and 2008 may well, in time, be seen as an anomaly. A historic aberration which could never last- but living inside the tail end of the boom is an unpleasant political, social, and cultural space to be.

Our fractured and destructive moment reminds me of the downfall of the landed aristocracy in the early 20th century. Outside of Downton Abbey, and its peculiar, if very British, interpretation of the landed estate, the change in circumstance and economy represented a historic shift- a generational change which all too many people found difficult to digest. The certainty provided by landed institutions was replaced with meritocracy. It was fairer and provided the space for so many people to rise, but it also left something behind. That thing is precisely what is lauded in Downton Abbey, a sense of the virtuous and duty to care, which we may reflect is missing today.

What replaced that world was vibrancy, forward thinking, and change previously unimaginable. In essence, a conservative’s worst nightmare. Given what has happened, it is perhaps little surprise that we are witnessing a backlash the like of which liberal democracy has rarely seen. Of course, counter-revolutions in the early years of democracy and liberal democracy were common and remain a threat in democracies which are newly formed, such as Tunisia and Egypt, following the downfall of their dictatorships. However, rarely have we seen institutionalised, long-lasting, and stable liberal democracies come under severe attack internally.

It was previously maintained that liberal democracy had only receded in countries with dire economic circumstances; that is, once economic sustainability had been achieved then people’s propensity for freedom would naturally run its course. This attitude can be summed up during the painful exchange between Charlie Kirk and a Cambridge student. The student argues that people naturally leap towards freedom, as demonstrated by reforms such as increased abortion access, increased equality of employment opportunity, and the charge to reduce sexism structurally. People are naturally happier when they have more choice.

Yet, both the student and Kirk failed to grasp the distinction between liberty and freedom. Unlimited choice, far from freeing us, paralyses most of us. Of course, people are also generally miserable when they have no choice; dictatorships are not known for smiling populations, unless you are a North Korean on parade, that is. Yet, the promise of self-fulfilment via increasing the levers of choice has also not really produced truly happy populations. Although just as some may thrive when they have unlimited choice, others may also thrive when they don’t have to decide. Heavy is the head that wears the crown and all that. We may consider that there are other factors, aside from choice, that lead to happiness, or indeed that happiness is not something that can be quantified or that it should be our primary life goal.

Thus, both Kirk, in defending limiting choice, and the student, in defending unlimited choice as the route to happiness, presented us with a false dichotomy. The question is not the amount of choice but the reality of that choice being enacted and the context in which we are situated. Kirk was right when he lamented that the notion of success was based on materialism, but he was wrong when he tried to reframe it via the opposite logic. People aren’t miserable because they have success or focus on their careers, but neither will they suddenly be happy if they have babies or acquire the choice to do both.

This is the problem affecting both modern liberalism and conservatism- a false fight over the right to choose as the road to happiness. It is not the right to choose which is the primary problem, but the world in which those choices are made, and the effects that those choices have on the body and soul of people. The fight over the right to choose is a secondary question which misses the primary discussion over the virtue of happiness itself.

Life is difficult, and if you have read much intellectual history, you realise misery is widespread. I have always wondered if misery is actually the condition in which a large portion of humanity has lived for most of the time. Perhaps we are only discovering this now because of large data sets. Huxley’s caution over drugs, sex, and liquor in Brave New World could be read as a caution against the abundance of mechanics that make us so happy that we are willing to fritter away everything else in its pursuit. Happiness and its unbounded quest, much like immortality, can lead us to oblivion just as much as any megalomaniac.

This false axis of choice has helped spark a renaissance of reactionary thinking that has filled our airwaves and hit our screens. If liberalism has given us unlimited choice and it has led to misery, then we must begin the fight back against choice as that will make people happy. Choice vs order is the traditional battle line upon which conservatism and liberalism are drawn. This is the distinction between seeing people as beings who are able to think their way through problems and emerge victorious, or those who argue we must trust the limits of our own knowledge and refer back to those who have come before us to guide our actions.

Although conservatism, with its suspicion of rationality, oftentimes is associated with or itself associates with a lack of ideology, it would be a mistake to accept such claims. The phrase, often attributed to Voltaire, that ‘common sense is not so common’ highlights the limitations of simply declaring conservatism is the standard bearer of the everyday. As Jason Blakely argues in Lost in Ideology, conservatism, akin to socialism and liberalism, makes claims about human nature, the best way to organise society and the capacities of the person. Therefore, it is not merely ‘common sense’ but an active way in which to organise society, just like liberalism and socialism are.

Not merely wedded to common sense, conservatism, as Andrew Heywood writes, is a system that believes in tradition. Perhaps best personified by Edmund Burke’s quote that society is a ‘contract between the living, dead, and those yet to be born’, the conservative attachment to tradition is a strong one. The reactionary writer Chesterton located the value of tradition in the wisdom of the past. But this did not mean an unchanging spirit; the paradox of conservatism, as Chesterton saw it, was the need to change while respecting the past. Tradition, if it wants to be maintained, cannot only be passed on but also be kept alive in the spirit of an ever-changing world. This is why those who argue conservatism is screaming at the world to ‘stop’ are wrong; they are asking the world to slow down.

Of course, at its worst, this desire for stability invokes bigotry against migrants, sexual minorities, transgender people and those who challenge social norms. These conservatives are swivel-eyed bullies eagerly looking for their next target, existing under the thin disguise of ‘family values’. Conservatism at its worst deserves the title of the ‘unthinking man’s party’ that J.S. Mill gave it, but we should not judge its record by its most unthinking members. Robert Jenrick is a stunning example of the danger of this bigotry masquerading as an ideology.

But we could look upon this impulse sympathetically. For all the danger of preferring order to innovation, can we really deny the danger of unlimited change? Are political orders really able to cope with mass shifts at unprecedented rates? It is an odd assumption to think that we can, given that in almost every area of our lives, we prioritise the passing of time to acquire wisdom. If we have a painful breakup or loss of a loved one, we recognise our reactions to those events are likely to be bad for us and those around us. Our friends, family, and colleagues advise us to give it time, and we can see the wood for the trees. But why should this not apply to our political lives as well as our personal ones?

Perhaps, just as in our personal lives, in our political lives, man cannot be trusted to always make the right decision without firm guidance and a structure to help them decide. Thomas Hobbes reflects this fear. Hobbes does not easily fit into the tradition of conservatism because of his belief in human rationality to form a political order, as well as his willingness to tear down the divine right of monarchy. However, many consider him a conservative because of his pessimistic view about what we do on our own terms. As Michael Oakeshott recognised, the vulgarities and ambitions of man were what Hobbes noted would be our downfall unless we agreed to surrender to the higher power of the sovereign. Hobbes is oftentimes misrepresented as the defender of the sovereign at the expense of all else. As he writes in his Dialogues, Hobbes is careful to tell rulers to obey ‘natural justice’ if they seek to remain a legitimate ruler lest they fall prey to the same impulses as pre-modern man. Even the sovereign is not fully trusted to find their own path.

This fear of nihilism, i.e., the absence of all values, which conservatism should seek to rein in, is reflected in Weber’s Politics as a Vocation lecture. The search for certainty in politics is a never-ending one, especially for conservatives who refuse constant questioning as an adequate grounding for a polity. Yet, for Weber, those searching for an answer will be left wanting and towards dangerous expectations of what politics can grant a person. Power should be used cautiously, and the exercise of it is always embedded with pacts with the devil. Power to enforce the state and ideology is, for Weber, a necessary evil and rarely, if ever, a truly settled matter.

This is why Carl Schmitt’s desire for order and authority to be restored via a reclamation of the tensions in politics manifested in a sovereign remains so dangerous. Far from securing political life, the excess of desire for order creates the paradox of destroying it. Conservative attacks on liberal permissibility only cohere if the ideology of conservatism can adequately answer them within the confines of reasonable alternatives. Currently, conservative movements appear to be swinging ever further away from the reasonable and towards artificial constructions of the past and ever greater authoritarian tendencies.

The desire for self-preservation is a strong one, as Hobbes supposed, but so is our desire for annihilation, even if we do not consciously acknowledge it. True, the notion of the right for us to sell ourselves into slavery, or vote in a despot, may be intellectually facile, but that does not restrain people’s impulses to do so. Unfettered choice, such as over the right to die, reaches the very tip edges of liberal acceptability without regard for outside actors or the boundaries of a civilised society. Conservatism in these moments should offer a genuine riposte to a liberalism that makes life and death a choice up for grabs.

More modern formations of conservatism, or rather American framings of conservatism, have not adhered to the logic of tradition alone, nor delivered on its earlier promise. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the fusion of Anglo-American conservatism, which has produced a confused melange of ideology. Simultaneously decrying migrants for moving to new countries, lgbt people for expressing their true selves and judges for enforcing the law, while simultaneously cheering on destructive market forces…

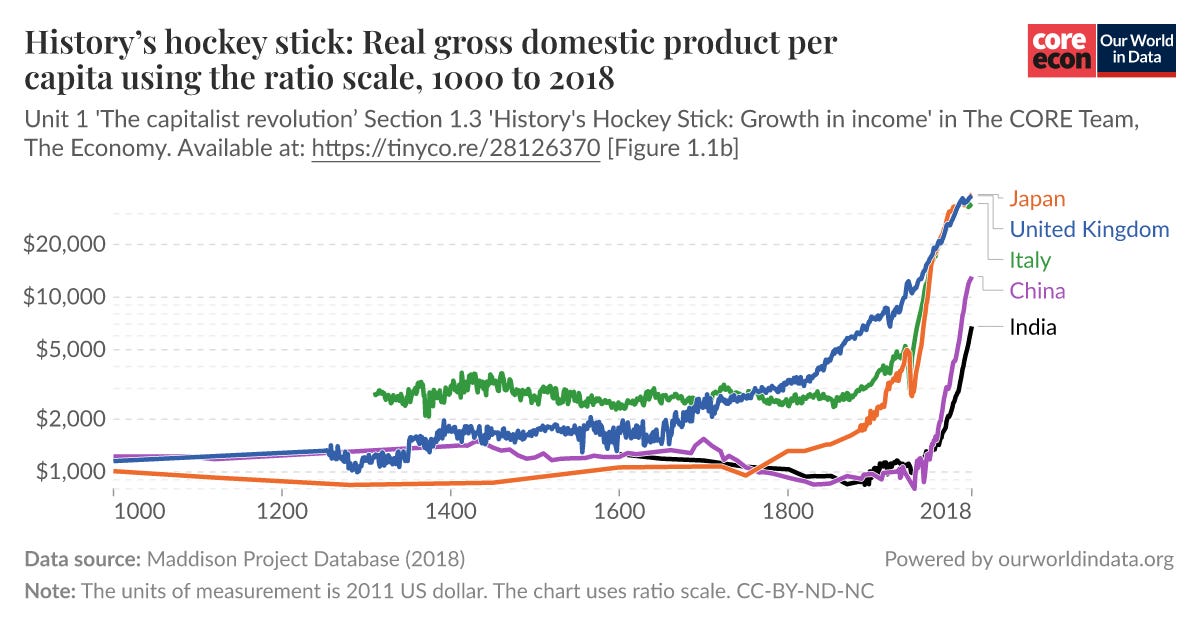

Modern conservatism has hardly been willing to slow down capitalism and all the creative destruction that comes with it. Capitalism, which upends social relations, cultural traditions, and the traditional distinctions between money and politics, has been greeted by conservatives with huge cheers. Lame attempts to call market capitalism ‘natural’ to sustain its conservative credentials ignore the hockey stick graphs, which show just how recent mass accumulation of resources really is. So much for tradition and rootedness.

To pose a genuine intellectual challenge to liberalism, conservatism must first find its own identity. More serious scholars such as Yoram Hazony and Patrick Deneen can offer genuine alternatives to the still dominant liberal order. But radical talk-show hosts are drowning out these more thoughtful attempts to construct an intellectual conservatism, and the arrival of a second-term Trumpism, which is even more cataclysmic than the first version, should make us all wonder what is happening to conservatism.

Naturally, this has led authors such as Corey Robin to conclude that conservatism is inherently reactionary, rooted in its opposition to the French Revolution, it is a tradition that is defined by its dislike of change. This narrow view lumps Churchill in with Carl Schmitt, Edmund Burke with Barry Goldwater and Georges Sorel with George W Bush… Although Robin acknowledges distinctions between conservatives, he fails to fully articulate the genuine distinction between conservatives who wish to preserve the existing political order (Churchill) and those who are willing to dismantle it in the hope of something truer and more vital emerging (Schmitt).

This perspective is a mutation of an ideology which the more thoughtful conservatives, such as Roger Scruton, railed against. But the conflation of conservatism across the US and the UK is heralding not only a new, confused form of ideology, but a pernicious one too. Authoritarian strains of conservative thought are nothing new. Isaiah Berlin labelled one of the first conservatives, Joseph De Maistre, as the first fascist for his hatred of the French Revolution and demand for the restoration of the monarchy. De Maistre, who believed in submission to the monarch and faith, represented a much uglier, reactionary conservatism than someone like Burke. Neither can we ignore the historical record of conservative thinkers and actors across the continent fighting against the vote to be given to ordinary people, women, and, in America, people of colour. The desire to maintain order has frequently come at significant costs within the conservative tradition.

But this battle between reaction and value within conservatism is a very real one when we see deformed versions of conservatism, such as Trumpism, where rule by the one masquerades as a return to tradition. As Mark Sedgwick highlights in Traditionalism: The radical project for restoring political order, many modern forms of the new right do not adhere to tradition as a starting point. Modern British-American conservatism is not looking to Scruton or Macintyre, but instead are cribbing from Dugin, Schmitt, and Bannon. Yet, these diverse intellectual threads somehow converged on the right with ripping up the administrative state while either calling for the expansion of migration laws, executive power, and defunding opponents inside the bureaucracy.

For this, we cannot look to notions of the ‘woke right’. Instead, writers such as Rick Perlstein, David Neiwert, and John Ganz have charted the intellectual decline of American conservatism into the nadir of conspiracy theories which are now infecting UK conservatism within the form of the right of the Conservative Party and Reform UK. Lacking substantial values beyond populist personalism, these are not answers but second-rate reactions to the genuine problems that plague liberal democracies.

Conservatism is in crisis. It has failed to answer the problems of our times and has instead doubled down on its very worst tendencies. If conservatism wants to survive, it must find its way through to values beyond an appeal to the frustrations and hatreds of our societies. It must see the value of our traditions and apply them to a dispiriting world. There’s nothing to stop conservatism from doing this apart from activists and party leaders.

All conservatism is based upon the idea that if you leave things alone you leave them as they are.

But you do not. If you leave a thing alone you leave it to a torrent of change. If you leave a white post alone it will soon be a black post. If you particularly want it to be white you must be always painting it again; that is, you must be always having a revolution. Briefly, if you want the old white post you must have a new white post.

(GK Chesterton on Conservatism)

Brilliant peice Sam. Explained perfectly.